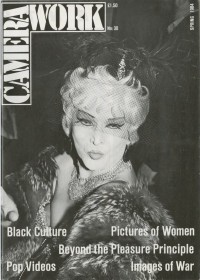

Articles

Ron Peck's Nighthawks

Extract:

Ron Peck’s 1978 film Nighthawks is commonly cited as the first explicitly gay British film, focusing on the life of a homosexual man and his interactions within the gay community. The film is a time-capsule of a particular moment in British queer history, capturing a kind of limbo that followed decriminalisation, but preceded the ravaging effects of the AIDs crisis. This moment has often been portrayed as a high point of sexual freedom and hedonism: a rare time when queer sex would not result in death or imprisonment.

Jeopardy is one thing totally lacking in Nighthawks. This makes it an odd watch in hindsight, so conditioned is the twenty-first century viewer to tales of queer love that end in death or dramatic upset. In contrast, the stakes are fairly low, and Jim’s life and erotic encounters are almost self-consciously banal: after all, the protagonist is a geography teacher.

Jim’s time on screen is an endless carousel of cruising and teaching: two sets of repeated patterns of behaviour and encounters that he performs with almost clockwork rigidity. Lovers and pupils come and go, but his side of the interaction remains the same; unable to form any lasting connection, Jim is frustrated both in the club and the classroom. This frustration is encoded in the form of the film itself: the same shots reappear time and again, and the music that pulses through the clubs and bars (even following Jim to his work party) is a fatigued repetition of a synthetic beat.

This dourness appears honest. Peck drew on his own experiences as a queer man in London, as well as canvassing the gay press for collaborators and tips. Derek Jarman provided the locations, and appears loitering in one of the bars. From these connections, the film receives little vignettes and pockets of real character, often from the minor figures in Jim’s life: his lovers and pupils. However, whilst non-actors can be refreshing in their truthful portrayals, this naivety can be lost beneath clumsy performances. The camerawork too teeters on the obvious. Michael Powell’s advice to Peck not to be afraid of showing the male gaze seems to have been taken literally by the director: the camera alternately stares down punters at a gay bar, intercut with close-ups of Jim’s watching eyes.

This can make for an awkward watching experience, particularly for audiences used to the slick professionalism of high-budget Hollywood. But Nighthawks’ clumsiness is part of its charm: the fact that it revels in its making is wonderful, making the viewer constantly aware of the effort it took to bring this story to the screen, and how experimental it was - both in form and content. Indeed, awkwardness is the mark of Jim’s existence as a queer man. In the twilight of prejudice, he is tolerated by his headmaster, but no more. Forced to lead a double life, he exists in a kind of limbo from which his retreat into the Soho bars and clubs provide no respite; never able to move into a steady relationship Jim is romantically hamstrung too.

The dramatic crux of the film is the explosive collision of these two lives as Jim ‘comes out’ to his class. The necessity of his secrecy is never clearer than when his private life becomes the subject of childish mockery. But Jim welcomes this transparency: he sees an opportunity to educate and discourage prejudice, remaining stoic in the face of his students’ vicious homophobia. It is a very raw scene, shocking in its malice, largely filmed from Jim’s perspective forcing the viewer to stare down his would-be tormentors as they jeer, titter and whisper amongst themselves. There are the old homophobic standards, accusations of child molestation, the assumption of cross-dressing, the fear of infection or conversion - uncomfortable echoes of Section 28 before its time.

Few children speak up in Jim’s defence, offering curiosity rather than contempt. Those that do are shouted down as gay themselves, or worse, as ‘teacher’s pet’. This reveals Jim’s conflicted position: his supposed authority as a teacher is undercut by his charges’ perception of a potential weakness to exploit, but his standing as a teacher is not much respected anyway and it is through his calm answers about his sexuality that we see his real strength.

Nighthawks is a film concerned with the paradoxes of gay life. At one point Jim and his friend Judy weigh up the various merits of non-monogamy: freedom is pitted against insecurity. Jim’s exhaustion during this debate is palpable; he seems aware that he is trapped despite the appearance of ultimate agency. Even after his breakthrough at school, the cycle persists. He must leave his lessons as they are - sex education is the only appropriate place for such discussions, though we know it will remain resolutely heterosexual - and his lonely cruising continues.

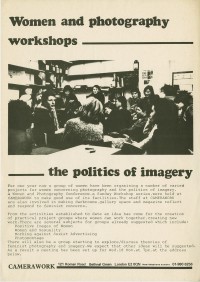

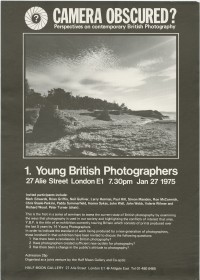

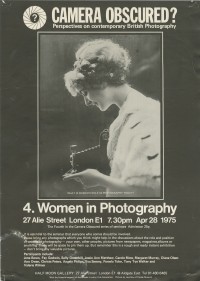

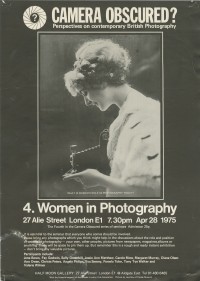

Women And Photography Workshops: The Politics o...

A flyer for a series of workshops on women and photography

Are Spinsters women without men?

Four Corners flyer for four screenings on gender relations, including excerpts from Mary Daly's '...

Testimony - Brenda Agard, Ingrid Pollard, Maud ...

Colour photograph of the outside of the gallery at night during the exhibition

Testimony - Brenda Agard, Ingrid Pollard, Maud ...

Colour photograph of reception desk inside the gallery during the exhibition

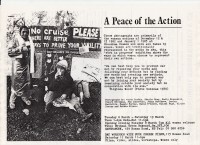

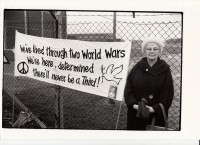

A Peace of the Action - Anita Corbin, Sheila Gr...

Black and white photograph of an old lady in front of a banner, exterior

David Hurn Photograph

Photograph of a bride and groom outside with family and friends throwing confetti

Oral History Excerpt - Jill Pack

Pack reflects on an initiative with group of women who were published in Camerawork and later rep...

Oral History Excerpt - Val Wilmer

Wilmer reflects on Half Moon’s Women Photography exhibits and theory vs “going along” with repres...

Oral History Excerpt - Val Wilmer

Wilmer discusses her involvement with Camerawork’s seminars, unpublished work for Camerawork Maga...

Oral History Excerpt - Julia Meadows

Meadows reflects on the success of the two women’s exhibitions as the start of Half Moon’s shift ...

Oral History Excerpt - Julia Meadows

Meadows discusses the origins, creative process and reception of Half Moon’s first Women’s exhibi...

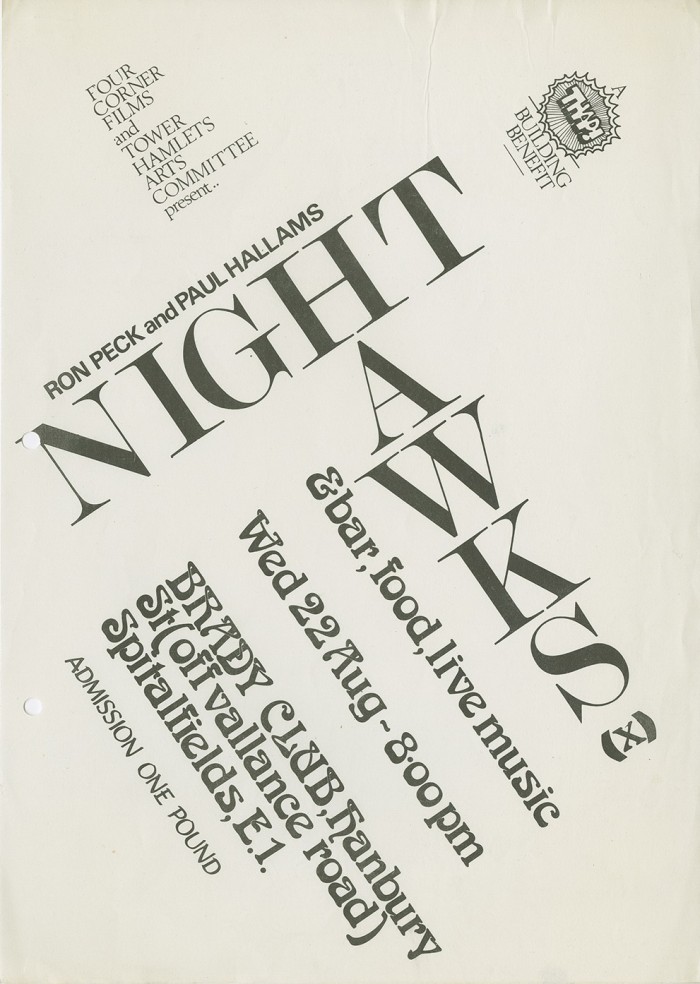

Oral History Excerpt - Ron Peck

Peck discusses the development of the film ‘Nighthawks’, Britain’s first feature film about the g...

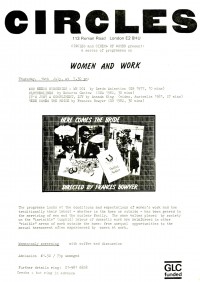

Oral History Excerpt - Lis Rhodes

Rhodes on how Circles used to advertise women only screenings, and how that helped with the confi...

Nighthawks - Ron Peck & Paul Hallam

Directed by Ron Peck, assisted by Paul Hallam, Nighthawks was the first British fiction feature w...